Ah, hello. Well you’ve had a look around my house and seen a little of the way we used to live in Verulamium. I suppose now you would like to know a little more about me - the skeleton that lies before you.

Well, when I lived here with my family in AD 200, Verulamium was a key junction in our Roman road system just 26 Roman miles up Watling Street from the capital Londinium.

Now Watling Street is the A5183 to the M25 and it was here off Watling Street that I was buried, outside the city on a hill. My particular plot was in a prime position as befits my status: close enough to the road for passers-by to admire the quality of my grave marker which once would have stood here.

Of course I wasn’t the first to be buried here. For over 200 years this was a popular cemetery. During that time many of my fellow citizens were cremated, their ashes were put into pots like these, then buried. But in the Roman Britain of AD200 important people like myself liked to do things with a little more style. That’s where the story ended for me and begins for you.

Since the 1930s, archaeologists have known about our old Roman cemetery, though locally it was called St Stephens after the present day Christian parish. They decided to leave the site un-excavated and let us Romans lie. Then the site got planning permission for new homes so the archaeologists got to work.

At first they found over 30 cremation pots of the type I was telling you about earlier. Then to their surprise and mine, they discovered my coffin.

After 1600 years in the earth my coffin was in a pretty delicate state even though it had been made from lead of the highest quality mined in the Mendip Hills. They brought the coffin and me inside it here to the Verulamium Museum.

Then in her studio Clare Pollack measured it up and recorded all the lavish decoration. My coffin as befits my status had the finest quality detail. For us Romans, the scallop shell pattern was a symbol of life after death. It represented the oceans across which we had to sail to reach the blessed isles after we died. It was fashionable throughout the Roman Empire. And all that’s finished off with a beading highlight - rather grand!

Once Clare had finished admiring the quality of the workmanship, (some of the finest that’s yet been uncovered in Britain as it happens), the next step was to look inside. Once again it required the hands of many.

Of course my flesh had long since disappeared, although my family had paid for my body to be packed in chalk to help preservation. All that was left were my bones and some linen imprints from my clothing. But to the credit of my funeral director my actual bones were in very good condition.

It was my bones that really gave the archaeologists the clues as to who I was. They knew I was male from the shape of my bones in particular the larger brow on the skull and the narrowness of the bones at the back of my pelvis. When it came to working out my age, they started with my teeth. They were quite impressed. In the first place, I had lost only one tooth and had only two cavities in my upper molars - not bad for a Roman. And the lack of wear on my teeth indicated a young man.

But they changed their mind when they saw my thyroid cartilage which had ossified. The older the person, the more this cartilage becomes bone. As you can see mine is pretty solid. Suddenly it was clear that I was older than they first thought, probably about 50.

Why were my teeth in much better condition than the average Roman Briton? It was because I ate better food. I could afford the freshest seafood from the coast, oyster, fish and lobster. These ragged marks on my vertebrae show that I suffered a little from arthritis on my spine but it was nothing that bothered me particularly. They even found out I couldn’t bend my little toe, the joint had become solid.

As to how I died, they really don’t know. The cracks on my skull suggest that I may have been hit on the side of the head, but I can’t really remember and the archaeologists can only guess.

You wouldn’t have thought that there was much more to investigate, but you know what archaeologists are like...

Never satisfied, they took my skull off to Richard Neave in Manchester by train. His speciality is finding out what people looked like purely by working from their skull. Over a period of several weeks he carefully rebuilt the muscles that made up my face by following the contours of my skull. He could even work out the size of my nose by measuring my nasal cavity. And the result you see before you - very clever.

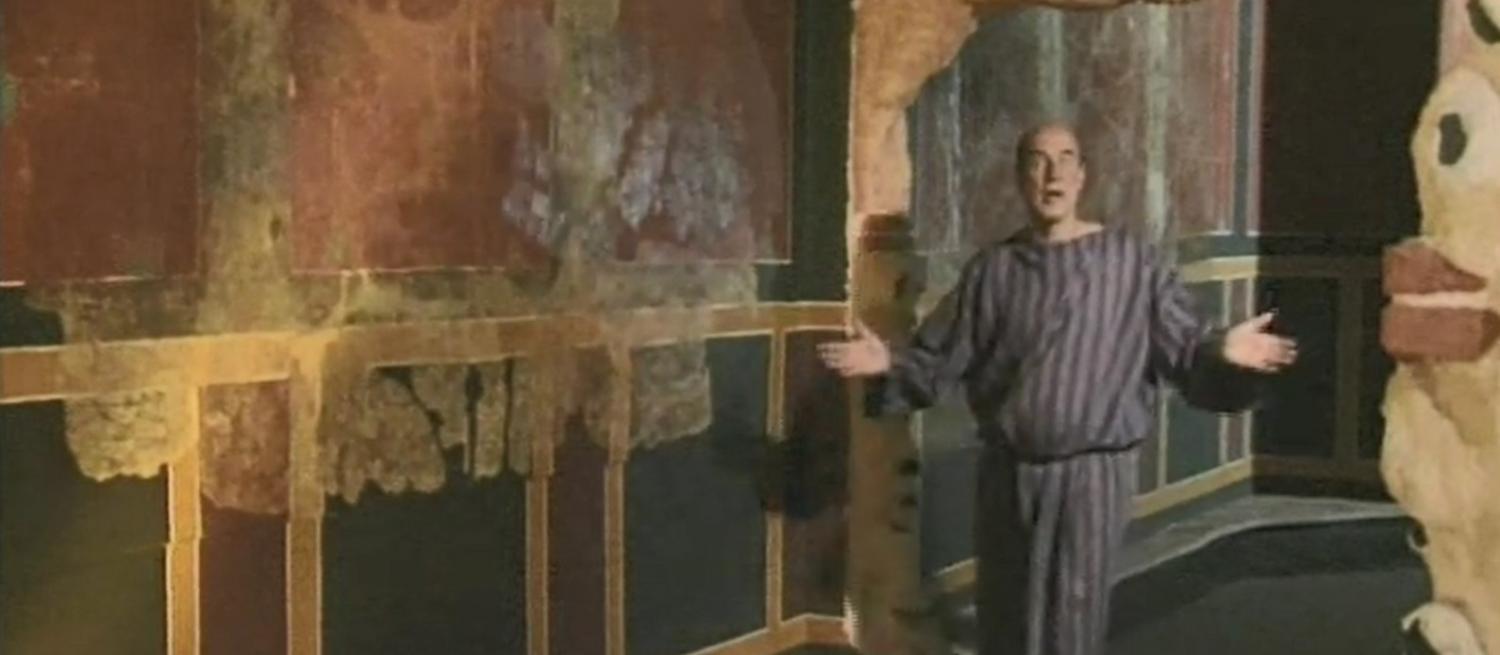

So here I am. Well, skeleton and bronze at least. Preserved forever in the Verulamium Museum surrounded by memories of the life I used to lead.

As I always said, why rush out to see the world when you can sit and let the world come to you.